The AI Inflection Point: Bubble, Boom, or Structural Shift?

- Mansa Kumar

- Dec 15, 2025

- 18 min read

I. The Counterintuitive Truth

Here is a proposition that will strike most as absurd: relative to the scale of its ambitions, the artificial intelligence industry is underspending. Not by a small margin, but dramatically so. When measured as a percentage of global GDP, current AI infrastructure investment of approximately 1% is roughly one-quarter of the capital intensity that characterised the UK railroad boom of the 1860s, which reached nearly 4.5% of GDP. The US railroad expansion exceeded 3%. Even the electrification of America in the 1920s surpassed 2%. By historical standards, the supposedly reckless AI buildout is remarkably restrained.

And yet. OpenAI has made investment commitments to industry counterparties totalling $1.4 trillion despite never having turned a profit. Nvidia has announced plans to invest $100 billion in OpenAI, whose primary expense is purchasing Nvidia chips. Thinking Machines Lab, founded by a former OpenAI executive, raised $2 billion at a $10 billion valuation without releasing a product or even disclosing what it was building. As one investor who met with the founder reported: "It was the most absurd pitch meeting. She was like, 'So we're doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can't answer any questions.'" Two months later, the company was reportedly in talks to raise at a $50 billion valuation.

Both propositions, the historical modesty and the speculative excess, are simultaneously true. This is the central puzzle of the current moment, and it cannot be resolved by the binary framework that dominates financial commentary. The question "Is AI a bubble?" is the wrong question. The right question is: What kind of bubble is it?

Bar chart comparing AI capex as percentage of global GDP (approximately 1%) against UK railroads 1860s (4.5%), US railroads 1880s (3%+), US electrification 1920s (2%+), US telecom 1990s (1.5%). Source: Goldman Sachs

II. Toward a Taxonomy of Speculative Excess

The financial history of technological transformation suggests that bubbles are not a single phenomenon but a category containing fundamentally different species. Some bubbles leave lasting infrastructure despite destroying investor capital; others leave only debt and recrimination. The analytical challenge is distinguishing between them before the outcome is known.

The Productive Bubble

The British Railway Mania of the 1840s remains the canonical example of what might be termed the productive bubble. Investors poured capital equivalent to over $3 trillion in today's terms into railway construction. Share prices ultimately fell 50%. Dividends delivered just 1.83% versus the 10% promised. As The Economist observed in 1855: "Mechanically or scientifically, the railways are an honour to our age and country: commercially, they are great failures."

Yet here is the crucial fact: the 6,220 miles of track built during the mania years form approximately 90% of Britain's current railway system. No one tore up the railways. The infrastructure survived the companies that built it, and the economic transformation it enabled dwarfed the capital losses of the speculators who funded it.

The dot-com bubble follows the same pattern. Telecom companies raised $1.6 trillion and floated $600 billion in bonds, laying over 80 million miles of fibre optic cable, representing 76% of all digital wiring installed in the US to that point. By 2001, only 5% of installed fibre was in use; bandwidth costs subsequently fell 90% within four years. This overcapacity enabled YouTube, Netflix, and cloud computing, businesses impossible at pre-bubble bandwidth prices. Fred Wilson, the venture capitalist who lost 90% of his net worth in the crash, later observed: "Nothing important has ever been built without irrational exuberance. All those ideas are working today. I can't think of a single idea from that era that isn't working today."

The Extractive Bubble

The 2008 housing crisis represents the opposite category: the extractive bubble. The financial engineering that inflated mortgage-backed securities created no durable productive capacity whatsoever. When the structure collapsed, it left behind foreclosed properties in exurban wastelands, $17 trillion in destroyed household wealth, and a financial system that required government rescue. The special purpose vehicles, structured investment vehicles, collateralised debt obligations, and credit default swaps were pure financial abstraction, untethered to physical infrastructure.

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 provides an even starker example. The South Sea Company's actual trade with South America was negligible; the entire scheme was financial engineering around government debt restructuring, with circular financing mechanisms where the company loaned money to investors to purchase its own shares. When the bubble burst, with shares falling from £1,000 to £100, it left virtually nothing productive behind.

The economist Carlota Perez captures the distinction in her framework of technological revolutions. "When financial capital takes the economy on a frenzied ride up a paper-wealth bubble," she writes, "the new and modernised production capital will be ready to take over and lead a more orderly growth process." The key word is production. Productive bubbles, for all their waste and destruction of investor capital, fund the installation of infrastructure that generates value for decades. Extractive bubbles merely redistribute wealth upward before collapsing.

Conceptual diagram showing two-by-two matrix: X-axis represents Infrastructure Intensity (low to high), Y-axis represents Credit vs Equity Funding. Quadrants classify historical bubbles: Railway Mania (high infrastructure/equity), Dot-com (high infrastructure/mixed), Housing 2008 (low infrastructure/credit), South Sea (low infrastructure/credit). Source: Mansa Kumar

III. The AI Paradox: Profitable Companies, Speculative Structures

The AI investment cycle presents a genuine analytical puzzle: it exhibits characteristics of both productive and extractive bubbles, depending on which layer of the market one examines. This is not a single bubble but a stratified phenomenon, with fundamentally different risk profiles at each level of the value chain.

The Hyperscaler Foundation

At the infrastructure layer, the current cycle rests on a foundation of genuine profitability that distinguishes it sharply from previous technology bubbles. The tech sector's free cash flow margin hovers near 20%, more than double its level in the late 1990s. Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, Alphabet, and Apple collectively generate hundreds of billions in revenue and possess substantial cash reserves to fund research and development without relying on speculative capital. As J.P. Morgan Asset Management notes, this investment is "largely financed by profitable, cash-rich firms and underpinned by robust demand."

The valuation metrics tell a clarifying story. Cisco Systems, the largest company in the S&P 500 when the dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, traded at a price-to-earnings ratio exceeding 200. Its earnings grew from 15 cents per share in 1996 to 36 cents in 2000, "paling in comparison to its rampant price appreciation," as the New York Times noted. Today, Cisco is valued at roughly $300 billion, still less than investors had valued the company a quarter-century ago.

Nvidia's trajectory has been notably different. Its P/E ratio peaked at over 200 in 2023, matching Cisco's at the height of the mania. But unlike Cisco, Nvidia's earnings have grown to meet its valuation; the current P/E sits around 45, with forward estimates dropping to approximately 25. NVIDIA's data centre division has posted 66% year-on-year growth, and at one point AI-driven demand fuelled a 262% year-over-year revenue surge. The company recently reported $32 billion in net income, up 65% in a single year. As Alex Altmann, head of equities tactical strategies at Barclays, observed: "The ability for Nvidia to continually meet lofty earnings expectations has been remarkable. It's almost unbelievable."

Goldman Sachs has argued that enthusiasm for AI "does not represent a bubble" in the traditional sense, precisely because valuations now sit on top of strong profit fundamentals. The Magnificent Seven trade at 38.3x trailing P/E versus the dot-com "Four Horsemen" (Cisco, Intel, Microsoft, Dell) at 82.7x at their 2000 peak. Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted the distinction: "They actually have earnings. These companies actually have business models and profits. So it's really a different thing."

The Mag10 now command over 35% of US market capitalisation (left), matching dot-com era concentration. Yet forward P/E ratios (right) sit at approximately 30x versus the 45-50x peak of 2000. The distinction matters: this cycle rests on earnings growth, not pure multiple expansion. Elevated concentration suggests fragility; reasonable valuations suggest sustainability. Both are true. Source: LSEG.

The Application Layer Trap

If the hyperscaler foundation exhibits the characteristics of a sound, if expensive, bet on transformative technology, the application layer tells a different story entirely. Here the structural dynamics push capital toward investments that cannot generate durable returns, regardless of how the underlying technology performs.

The AI investment pyramid reveals the mechanism. The infrastructure layer, with its massive capital requirements, mandates an oligopolistic market structure that keeps venture capital largely outside. As one analysis from the project files notes: "Incumbent hyperscalers already have the scale, and they see that the massive investment required creates huge barriers to entry, as it would be impossible for newcomers to reach profitable scale while burning hundreds of billions at the same time." Even neo-clouds like CoreWeave and Nebius are largely contractors of incumbent hyperscalers, reinforcing rather than challenging the oligopolistic structure.

The foundational model layer, while less capital-intensive, still demands investments of billions, accessible only to the largest funds. This pushes the broader pool of risk capital toward the application layer, where barriers to entry are low but opportunities for durable value capture are virtually non-existent. The problem is structural: the API layer provides no differentiation, and the software layer above it can be copied effortlessly. AI labs can break the stickiness of any vertical application simply by removing their markup on foundational model usage in their own products while maintaining it for external developers.

The result, as multiple analysts have observed, is that "dozens of billions invested in the application layer will likely never see a return." Sam Altman himself has called it "insane" that startups with "three people and an idea" are receiving funding at such high valuations. "That's not rational behaviour," he observed. "Someone's going to get burned there." Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google DeepMind, offered a similar diagnosis: "It feels like there's obviously a bubble in the private market. You look at seed rounds with just nothing being tens of billions of dollars. That seems a little unsustainable."

This is precisely the setup that gives rise to speculative excess. There is massive but fragmented capital that wants exposure to AI, but the attractive infrastructure opportunities are structurally closed to it. So capital flows into whatever it can find, driving valuations skyward for companies without defensible competitive positions or plausible paths to profitability.

IV. The Financing Hump and the Question of Minsky

BlackRock has identified what it calls the "financing hump": the temporal mismatch between front-loaded capital expenditure and back-loaded revenue realisation. The AI buildout requires immediate investment in compute, data centres, and energy infrastructure. The eventual revenue from that investment comes later, potentially much later. To bridge this gap, AI builders are increasingly turning to debt.

The numbers are substantial. External estimates of AI corporate capital spending ambitions range between $5-8 trillion globally through 2030, most of that in the US. BlackRock's analysis suggests that large tech firms will need to grow revenue faster than current projections for AI-driven investment to pay off, requiring $1.7-2.5 trillion in new AI-driven revenue to achieve a reasonable 9-12% lifetime internal rate of return. Meanwhile, the biggest spenders (Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Oracle) had only about $350 billion in the bank collectively as of Q3 2025.

Oracle, Meta, and Alphabet have issued 30-year bonds to finance AI investments, with yields exceeding Treasury rates by as little as 100 basis points. The question investors must confront is whether accepting three decades of technological uncertainty for such modest spreads constitutes prudent fixed-income allocation. Will the investments funded with debt, in chips and data centres, maintain their level of productivity long enough for these 30-year obligations to be repaid?

Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis provides the framework for understanding how this could go wrong. Minsky identified three stages of speculative finance: hedge finance, where borrowers can service both principal and interest from current cash flows; speculative finance, where they can cover interest but must refinance principal; and Ponzi finance, where cash flows cannot cover even interest payments and borrowers depend entirely on asset price appreciation to survive. His core insight was that "over periods of prolonged prosperity, capitalist economies tend to move from a financial structure dominated by hedge finance to a structure that increasingly emphasises speculative and Ponzi finance."

The warning signs that Azeem Azhar identifies in Exponential View are worth heeding: hyperscaler capex outpacing revenue momentum, vendor financing proliferating, coverage ratios thinning, and lenders sweetening terms to maintain deal flow. Paul Kedrosky points to a potential "Minsky moment," the inflection point when credit expansion exhausts good projects and begins chasing bad ones. "For AI infrastructure," Azhar writes, "the warning signs are flashing: vendor financing proliferates, coverage ratios thin, and hyperscalers leverage balance sheets to maintain capex velocity even as revenue momentum lags. We see both sides, genuine infrastructure expansion alongside financing gymnastics that recall the 2000 telecom bust."

Area chart showing projected AI capex (front-loaded, steep rise 2024-2028) versus projected AI revenue (back-loaded, gradual rise 2026-2035), with shaded gap representing the 'financing hump' that must be bridged by debt. Source: Mansa Kumar

V. The Circular Economy of Artificial Intelligence

The most troubling structural feature of the current cycle is the emergence of what critics call circular financing. The Bloomberg diagram illustrating the AI "money machine" reveals a web of interdependencies that simultaneously inflate valuations across the ecosystem without necessarily creating equivalent real-world value.

Consider the Microsoft-OpenAI-Nvidia triangle. Microsoft invested $13 billion in OpenAI. OpenAI spends most of this on Azure compute, with credits partially awarded as part of the investment. Microsoft pays Nvidia for GPUs to power Azure. Nvidia has announced plans to invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI. Meanwhile, Oracle is constructing $300 billion of OpenAI's Stargate data centres, spending approximately $40 billion purchasing Nvidia's GB200 chips to do so. OpenAI has inked a separate $300 billion cloud deal with Oracle.

Goldman Sachs estimates that 15% of Nvidia's sales next year will derive from such arrangements. Nvidia has provided a $6.3 billion backstop agreement with CoreWeave through 2032, committing to purchase unsold cloud capacity, effectively guaranteeing demand for its own products. OpenAI has made investment commitments to industry counterparties totalling $1.4 trillion, despite never having turned a profit. The commitments are structured to be paid from revenues received from the same parties.

Short-seller Jim Chanos poses the central question: "Don't you think it's a bit odd that when the narrative is 'demand for compute is infinite,' the sellers keep subsidising the buyers?" This raises the uncomfortable possibility that the AI industry has constructed something resembling a perpetual motion machine, where investment flows create the appearance of demand that justifies further investment.

Yet here is where the productive bubble framework complicates the analysis. Unlike the financial engineering of 2008, which created no physical infrastructure whatsoever, AI circular financing creates data centres, power purchase agreements, and GPU clusters. Meta's $300 billion Hyperion data centre financing through special purpose vehicles, with only 8.5% equity and $270 billion kept off-balance sheet, resembles the leverage patterns of structured investment vehicles. But the underlying assets are data centres and power infrastructure, not mortgage derivatives on subprime loans.

The analyst Gil Luria of D.A. Davidson draws the essential distinction between healthy and unhealthy behaviour within the sector. Healthy behaviour is practised by "reasonable, thoughtful business leaders, like the ones at Microsoft, Amazon, and Google that are making sound investments in growing the capacity to deliver AI. And the reason they can make sound investments is that they have all the customers... And so, when they make investments, they're using cash on their balance sheets; they have tremendous cash flow to back it up; they understand that it's a risky investment; and they balance it out."

Unhealthy behaviour, by contrast, describes "a startup that is borrowing money to build data centres for another startup. They're both losing tremendous amounts of cash, and yet they're somehow being able to raise this debt capital in order to fund this buildout, again without having the customers or the visibility into those investments paying off." The distinction matters enormously for understanding where risk is concentrated and where durable value may ultimately accrue.

Network diagram showing capital flows between Nvidia, OpenAI, Microsoft, Oracle, CoreWeave, AMD, and other players. Arrows colour-coded by type: hardware/software purchases (magenta), investment flows (cyan), services contracts (green), venture capital (grey). Circle sizes represent market capitalisation. Annotation highlighting $100B Nvidia-OpenAI investment, $300B Oracle-OpenAI deal, $6.3B Nvidia-CoreWeave backstop. Source: Bloomberg News reporting.

VI. The Physics of the Boom: Energy, Copper, and the Lasting Asset

There is a provocative argument that the most durable legacy of the AI boom may not be the software at all. One commentator in the project files puts it starkly: "A railroad track lasts fifty years; a GPU is a melting ice cube. If this bubble bursts in 2027, the silicon we are hoarding today won't be a gift to the future; it will be e-waste. We aren't building the tracks; we're building the trains, and the trains are rusting before they leave the station."

If there is a true "inflection" here, a legacy asset that survives the inevitable correction, it may be the voltage. The real constraint on AI is not intelligence; it is physics. To feed insatiable data centres, hyperscalers are forcing the utility sector into a modernisation it has avoided for decades. They are signing twenty-year power purchase agreements, restarting nuclear reactors, and hardening substations. They are using what one analyst calls "the infinite wallet of the bubble to bribe the energy sector into a supercycle."

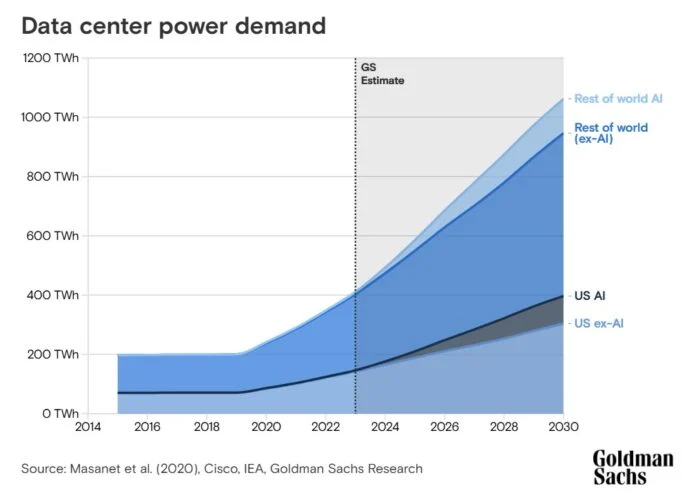

The numbers are staggering. Data centres already consume over 4% of US electricity, a share that BlackRock projects could reach 15-20% of current US electricity demand by 2030. Some estimates suggest data centres could consume a quarter of current electricity demand. The International Energy Agency projects global data centre electricity demand doubling from approximately 415 TWh in 2024 to 945 TWh by 2030, equivalent to Japan's entire electricity consumption.

Grid capacity represents the binding constraint. Average data centre development requires seven years from initiation to operation. Grid connection wait times now extend to similar durations for large projects. Goldman Sachs estimates $720 billion in grid spending needed through 2030. As BlackRock's Alastair Bishop observes: "Companies haven't struggled to get chips, the real constraint is land and energy."

Nuclear restarts signal the seriousness of power demand. Microsoft's 20-year power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy will restart Three Mile Island's Unit 1 reactor by 2028, providing 835 MW at a cost of $1.6 billion. Holtec International is working to repower Michigan's Palisades reactor by end of 2025, potentially the first US reactor to return from decommissioning. Amazon purchased a data centre adjacent to Susquehanna's 960 MW nuclear plant.

Copper demand presents similar supply constraints. Data centres are projected to require 400,000 tonnes to over one million tonnes annually by 2030. Hyperscale facilities use up to 50,000 tonnes each versus 5,000-15,000 for conventional data centres. The IEA projects existing and planned mines meeting only approximately 70% of 2035 copper demand. US mine development averages 29 years from permit to production.

When the hype recedes and the large language models encounter diminishing returns, the gigawatt-scale industrial parks will remain. The copper, the concrete, and the connection to the high-voltage grid do not depreciate in three years. "The venture capitalists think they are betting on a new species of software," one analyst observes. "History might look back and realise they were just the useful idiots who paid to re-industrialise the American power grid."

Chart showing Global data centre electricity consumption is projected to surge from approximately 200 TWh in 2022 to over 1,000 TWh by 2030, with AI workloads driving the majority of incremental demand. US AI-specific consumption (dark blue) is expected to grow from negligible levels to approximately 400 TWh, while rest-of-world AI demand (light blue) adds a further 200 TWh. The projection implies data centres could consume the equivalent of Japan's entire current electricity output by decade's end.

VII. The Agentic Horizon: Why the Bulls May Yet Be Right

The most forward-looking bull case concerns not current AI capabilities but the impending transition from passive chatbots to agentic AI systems. Most scepticism about the AI buildout is calibrated to conversational interfaces that summarise documents and answer questions. The industry, however, is pivoting toward systems that execute multi-step tasks autonomously: planning supply chain routes, debugging entire software stacks, managing complex workflows without human intervention.

UBS estimates that compute demand for chatbots will grow modestly, but demand for agentic AI is projected to explode to 19,627 exaFLOPs by 2030, dwarfing the requirements of today's applications. As one analysis notes: "This explains the 'disconnect' people feel today. Investors are looking at 2024 usage (the tiny dots). Hyperscalers are looking at the 2030 grey circle and screaming that data centres aren't big enough."

The productivity evidence, while early, is not imaginary. Some enterprises report 30-50% improvements in workflows by using AI copilots for coding, content generation, analysis, and support. Surveys suggest around 75% of developers now use AI code assistants. Less experienced engineers can sometimes produce near-expert-level output with AI help, effectively upskilling the workforce and compressing learning curves.

Economist Erik Brynjolfsson suggests that AI is likely following a J-curve common to general-purpose technologies: heavy investment and little payoff at first, followed by a delayed but steep productivity climb once organisations restructure around the new capabilities. Electricity took decades to show up in productivity statistics. The internet required new business models and processes. AI may still be in the "early, negative part" of that curve, with the real payoff arriving closer to the late 2020s.

Anthropic, one of the leaders in AI coding tools, has reportedly "10x-ed" its revenues in each of the last two years, representing 100x growth in two years. Revenues from Claude Code, a coding programme introduced earlier this year, are already said to be running at an annual rate of $1 billion. Cursor, another leader, saw revenues grow from $1 million in 2023 to $100 million in 2024, and they too are expected to reach $1 billion this year. These are not the revenue profiles of vapourware.

Gartner's framework captures the central tension in AI investment: provider capabilities are advancing far faster than enterprise adoption can absorb them. The shaded "Adoption Gap" represents the widening divergence between what AI systems can theoretically do (the innovation race toward agentic AI and beyond) and what organisations are actually deploying to generate returns (the outcome race, still largely anchored in traditional ML and early generative applications). Source: Gartner

VIII. Synthesis: The Fragile Boom and Its Discontents

Sam Altman has captured the essential tension: "When bubbles happen, smart people get overexcited about a kernel of truth. Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? My opinion is yes. Is AI the most important thing to happen in a very long time? My opinion is also yes."

Both propositions can be simultaneously correct. This is the analytical insight that the binary bubble debate systematically obscures. The railroads were a bubble, and they transformed Britain. Electricity was a bubble, and it transformed America. The broadband buildout of the late 1990s was a bubble, and it transformed the global economy. Given the scale of debt now flowing into AI infrastructure, it seems unlikely that AI will be the first transformative technology that is not overbuilt and does not incur a correction.

The taxonomy developed here suggests that AI occupies an unusual position: it is simultaneously a productive bubble at the infrastructure layer and a speculative bubble at the application layer, with the financing structures somewhere in between, exhibiting both the cash-flow backing of healthy corporate investment and the circular dependencies that preceded previous crashes.

The hyperscaler layer, funded by profitable core businesses and characterised by genuine demand for compute, represents a sound if expensive bet on transformative technology. The startup ecosystem, particularly at the application layer and among debt-funded infrastructure providers, exhibits the speculative excess and circular dependencies that have preceded every previous technology crash. The infrastructure being built, the data centres and power agreements and grid connections, will likely survive even if the companies building them do not.

Oaktree's Bob O'Leary offers the clearest framework for thinking about the risk: "Most technological advances develop into winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most competitions. The 'right' way to play this dynamic is through equity, not debt. Assuming you can diversify your equity exposures so as to include the eventual winner, the massive gain from the winner will more than compensate for the capital impairment on the losers. That's the venture capitalist's time-honoured formula for success."

"The precise opposite is true of a diversified pool of debt exposures. You'll only make your coupon on the winner, and that will be grossly insufficient to compensate for the impairments you'll experience on the debt of the losers." The proliferation of debt financing in AI infrastructure, particularly the 30-year bonds and SPV structures, represents an asymmetric bet in precisely the wrong direction.

Pyramid diagram showing AI investment layers from bottom to top: Infrastructure (hyperscalers, oligopolistic, equity-funded, defensible), Foundational Models (high capital requirements, concentrated, mixed funding), Application Layer (low barriers, fragmented, VC-funded, high failure risk). Annotation showing where value accrues (bottom) vs where speculation concentrates (top). Source: Mansa Kumar

IX. Positioning for the Correction That May Not Come When Expected

There is one final lesson from history that deserves attention. Alan Greenspan delivered his famous "irrational exuberance" warning on 5 December 1996, with the Dow at 6,437. The market more than doubled over the following three years before peaking in March 2000. Investors who sold after his warning forfeited a 105% return before the eventual crash brought prices back to December 1996 levels. Being fundamentally correct about overvaluation provided no timing advantage whatsoever.

Paul Christopher, head of global investment strategy at Wells Fargo, argues: "It's uncertain but still early. We are not at 1999, we think we can say that for sure." If he is right, abandoning AI exposure now risks missing substantial gains before any correction materialises. The investor's task is not to determine whether a correction will occur but to position for both the transformation and its inevitable dislocations.

The investment implications follow from the stratified analysis. At the infrastructure layer, the hyperscalers with their cash flows and customer relationships will likely emerge strengthened from any shakeout. BlackRock maintains a "pro-risk" stance on the AI theme, expecting it to become increasingly an active investment story as revenues spread beyond technology. The "picks and shovels" opportunity extends beyond semiconductors to utilities, grid infrastructure, industrial metals, and the private capital funding the physical buildout.

Listed infrastructure trades at a deep discount to public equities, below global financial crisis levels and comparable to the COVID-19 shock. This discount reflects uncertainty about interest rates rather than deteriorating fundamentals. For investors positioned appropriately, the AI theme is not merely about technology stocks but about the foundational industries that make the boom physically possible.

At the application layer, caution is warranted. The clearest excess lies in the private market for AI startups, where billion-dollar seed rounds have become normalised for companies with, in Ilya Sutskever's words, "more companies than ideas." The debt-funded infrastructure layer presents a different but equally concerning risk profile: rational for the lenders only if the technology delivers on its most optimistic projections, catastrophic if it delivers merely good results.

The most honest assessment may be Howard Marks's conclusion in his analysis of the AI cycle: "There is no doubt that investors are applying exuberance with regard to AI. The question is whether it's irrational. Given the vast potential of AI but also the large number of enormous unknowns, I think virtually no one can say for sure. We can theorise about whether the current enthusiasm is excessive, but we won't know until years from now whether it was. Bubbles are best identified in retrospect."

What the taxonomy can clarify is that the answer lies in physical infrastructure and real productivity gains, not in the stock prices of the companies building them. The hyperscalers will likely survive. The application-layer startups funded at absurd valuations will largely disappear. The infrastructure, the grid capacity, the copper and concrete, will remain. And in that remaining infrastructure, patient capital may find the genuine value that speculative capital is currently obscuring.

*

The AI inflection point is neither bubble nor boom in any simple sense. It is a stratified phenomenon, productive at the base and speculative at the apex, with physical constraints that will shape its ultimate scale and financial structures that will determine how losses are distributed when the correction arrives.

Comments